By: Jamaal Ryan

The Next Generation of Indie Games (7/29)

We’ve heard the rants from Phil Fish and the harsh

criticisms from Jonathan Blow, Microsoft’s penetrating publishing attitude has

turned away many indie developers. But since Microsoft’s second about-face, now

allowing indie devs to self-publish on Xbox One and enabling each console to be

their own dev kits, it is very clear that indie development is the new hotness

this generation, allowing freshly untainted minds to deliver unique and

potentially unconventional experiences.

The indie scene has been pioneered by PC for many years,

with many avenues in which players can engage them, whether that may be a free

download on the game’s website, or new community supported titles debuting on

Steam Greenlight. However many gamers, such as myself, don’t have access to

these titles out of avoidance of the PC as a platform.

Sony has already given many gamers the opportunity to enjoy

some of these games, such as Hotline Miami, Thomas Was Alone, and Stealth Inc.

But now with Microsoft entering the new era of indie game support, there’s no

telling what will grace our consoles in the future.

Perhaps we’ll see games with a more with more intellectual

subject matter; games like That Dragon, Cancer, which places you in lead designer

Ryan Green’s shoes as he tries to comfort his six year old son who’s suffering

from cancer, Papers, Please where you as an immigration inspector

has to control the flow of individuals while accepting or denying their

entrance to the city, and 9 Months

In, a game about a pregnant woman 9 months pregnant in prison.

This next console generation is equally about impressive graphical

fidelity, sound, the ability to topple sky scrapers and travel cross county in

a player populated United States as it is about low budget driven niche ideas

that introduce new ways to play and convey themes and storytelling.

Source: Polygon

The Inception of Video Game Consoles (7/30)

When we think of the development of next gen hardware, the

many of us are led us to believe that this is a process engineered in a closed

environment where the publisher signs deals with hardware component

manufactures and takes an occasional look at leaked information of their

competitors system features. It’s a process that we’re generally ignorant to,

typically relaying on pre-launch rumors and post launch executive

interviews.

In the book Dreamcast

Worlds, author Zoya Streets gives us insight into the development of the

Sega Dereamcast, offering perspective that grants us a better understanding on

the forces behind these games entertainment centers.

Streets describes the factors behind console development as

a network, stating that they consist of, “human developers, hardware components,

development tools, games, corporations, competitors, consumers, the media, and

more.”

In this very candid upcoming console generation, we can draw

similarities from these factors to what has driven console development today:

Sony’s outreach to developers asking what kind of system they would want to

develop for, Nintendo’s philosophy on engineering their systems around

particular game ideas, the consumer’s influence on Xbox One’s 180, and the

messaging of these systems themselves targeting multiple demographics.

There are many questions with unsatisfying answers about

today’s and tomorrow’s fast approaching hardware. Why was Sony so dodgey about making

announcements before and after Microsoft? Why didn’t Xbox One’s development

start until 2010? And why does Nintendo continue to release hardware with last

gen specs on next gen hardware?

Dreamcast

Worlds may not have the explicit answers we’re looking for, but it

might help us better understand the reasonings for these decisions.

Source: Kotaku

Wii U: The First Party Nintendo Machine (7/31)

Owning a Wii U as an additional console to any other current

gen systems likely entails you to have one primary interaction with it, wiping

off that thin layer of dust.

And if you only own a Wii U, then I’d ask you, what the hell

are you doing?

This week, we were introduced to Batman Arkham Origins

multiplayer mode, an interesting Splinter Cell influenced competitive mode to a

franchise that one would least expect to see supported multiplayer from. But in

addition to that announcement, we’ve also learned that outside of the 360, PS3,

and PC versions, the Wii U build of Arkham Origins won’t support multiplayer.

For the platform, this doesn’t come as a surprise as we’ve

seen features that existed in other multiplatform versions absent on Wii U.

From Sniper Elite V2’s co-op mode to Black Ops 2’s missing DLC. Third party

developers are have halted and pulled support from the system entirely. Ubisoft

pushed the previously Wii U exclusive Rayman Legends to release alongside the

360 and PS3 versions, and the critically divisive launch title ZombiU will not

have a sequel, a clear sign that Ubisoft meant business when they stated they

will not take a chance on games that won’t support franchises.

With numbers like

160,000 units sold globally in three months, we begin to better understand why

EA previously stated that they have no games in development (until they said

they did), and scratch our heads as to why Activision approved Call of Duty:

Ghosts to be released on Wii U.

The business perspective is simple, Wii U sales are light

and slow; investing in such a poorly performing console is not feasible.

As an owner of multiple systems, it’s nothing short of

foolish to choose the Wii U version of third party titles over any other

system, unless the developer explicitly highlighted exclusive perks. Splinter

Cell: Blacklist, Watch Dogs, and Call of Duty: Ghosts will release on Wii U

this year. But with the trend of lacking DLC and missing online features,

there’s very little reason to have faith that the Wii U build will be better,

or even comparable than versions on other platforms.

The games press has called the Wii the “Mario and Zelda”

system, and for now, it looks like the Wii U will follow the same trend. I’m

hanging on to my Wii U for Pikmin 3, The Wonderful 101, Donkey Kong Country:

Tropical Freeze, and New Super Mario 3D World; but given that E3 has shown us

that the industry has “next gen” development for the Xbox One and Playstation 4

in focus – on top of the lack of Wii U support we’ve seen even without these

systems out yet -- for the better part of 2014, my Wii U will be my go to

system for Smash Brothers, Mario Kart, and whatever other quality Nintendo

published titles release next year. But that’s just about it; nothing more,

nothing less.

Tropes vs. Women in Video Games Episode 3 (8/1)

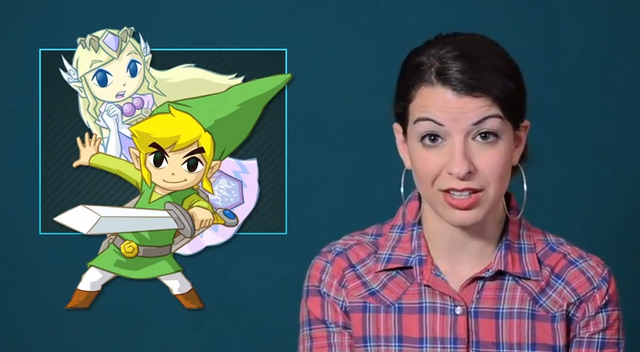

Anita Sarkeesian’s series Tropes vs. Women in Video Games

sociologically critiques the portrayal of women in video games, reviewing the

empowering, the disempowering, and the down-right chauvinistic roles women fit

in many of our favorite titles.

This week, Feminine Frequency posted Episode 3 which takes a look

at what games have done in order to recreate the damsel in distress relationship.

Anita dissects the stereotypes still shown in these recreations, and highlights

games that have approached this trope well.

There are a few games that have subverted the “damsel” and

hero relationship, games like 1990’s Balloon Kid, 2003’s Kya: Dark

Lineage, and more known cult hits such as Primal and Beyond Good

and Evil. Each of these games has missions or uses the primary story

thread that involves a female lead rescuing a male in distress.

Mario, the franchise that is the oldest contributor the

damsel archetype, had the spin off Super Princess Peach for the DS in 2006. Here,

instead of Mario looking for Peach in another castle, Peach is doing the

rescuing, looking to save both Mario and Luigi. And as empowering as this may

seem, Super Princess Peach falls into some glaring stereotypes. This is mainly

seen in her special abilities which involve her using emotional outbursts to

defeat her enemies. Essentially, she PMSs them to death.

Anita then discusses three approaches that developers have

taken to recreate or parody the damsel trope. The first sounds more like a cop

out, where the game follows the same formulaic beats as an old school rescue adventure

with the only disclosed defense is its attempt to highlight the zeitgeist of a

typical man saves woman dynamic. But even as a parody, this idea does nothing

to solve the problem or move us away from this stereotype. It reinforces the

trope, hoping the comic relief will excuse its nature.

The next two seeks to actively change the trope, but hardly

moves away from the stereotype. Many games such as Super Meat Boy reward the

player after beating the game by unlocking a female avatar as a playable

character. Yet it still doesn’t get away from having to play as the male lead

in the first place.

The third mentioned springs a surprise on the player once

they’ve beaten the game. Games like Earth Worm Jim where a cow falls and kills

Princess-What’s-Her-Face, like at the end of Eversion where the princess turns

into a cannibalistic monster and eats you alive, or like Castle Crashers where

one of the princesses shocks you with her clown face. The joke’s on you, but

you still spent 99% of the game ostensibly saving a helpless princess.

Few games get this right, like in Secret of Monkey Island

where the damsel you’re saving was completely capable of saving herself until

you ruined it, or Braid where the damsel you’re trying to save is actually

running away from you.

We’re seeing the role of empowered women more and more, like

in games such as Tomb Raider, Bioshock Infinite, The Last of Us and upcoming Beyond

Two Souls. The tropes are being subverted more rapidly than any other medium,

but we’re not quite there yet. With the presence of more and more women in game

development, game studios led by women such as 343 Industries, and the rise of

indie game development, we can look forward to seeing more inspirational representation

of women in tomorrow’s games.

A Week in Gaming Special Feature:

Minority Representation in Video Games

I came across a story a while ago that pointed out the coincidence on how many video game character leads looked too similar. They typically had low cut, mostly buzz cut hair, maybe a little bit of stubble, and had a fixed scowl on their face. Do you know what else they had in common? They were all White.

At the IGDA Summit in San Francisco, developers Mattie Brice and Kristen Finley spoke about how the lacking and misrepresentation of minorities in video games often reinforce stereotypes and create barriers to the connection players have with their characters.

Too often we see minority cast members in a game making it seem as if it was an attempt to diversify the “band of heroes” seeking to save the world… yeah, like Power Rangers (anyone find any issues with the Back Ranger?). Other times we see that member work as an interpreter for the main hero as a way to translate their alien and sometimes savage culture. While the former is seen as well intentioned, the later comes as a sometimes offensive result.

While the White male lead would hold the most nuanced, culture free behavior, characters of other races and/or cultures are packed into these rigid parameters to highlight what they have to contribute to the cause: The Black guy= the gangster and/or heavy hitter, the Hispanic and/or Middle Eastern= the gate keeper of language and culture barriers, the Eastern Asian= the one well versed in the secret arts of specialized combat, the woman=the healer.

With no imperial data to back this point, I would assume that minorities and females are more inclined to customize lead characters that more represent themselves than White males; Fem-Shep or Fem-Hawke, Black-Shep or Hispanic Hawke. I approach that hypothesis because we as minority gamers don’t see positive representations of ourselves in video games; whether that would be another damsel that needs saving, or a brutish Black male carrying a very large gun. The demographic that is the most represented in games might feel more comfortable creating an avatar characteristically antithetical to themselves because they don’t feel the sense of misrepresentation or lack of representation.

As is with every early area of growing pains this industry had developed through, racial representation has become increasingly subtle. These growing pains have been seen in characters such as Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas’ CJ. Though Rockstar always infamously portrayed elaborate caricatures, CJ was, and deliberately so, a stereotypical Black male in almost every way. We can already see that GTA V’s Franklin will carry the “hood” culture with him into the trio, but let’s hope that they treat him with a more personable level of care.

Much better than Final Fantasy XIII’s awful Sazh who fit nearly every stroke of a Chris Tucker-ish “You crazy for that!” jester, Final Fantasy VII’s Barret Wallace, beyond his muscular, heavy gun totting stature and deliberately slanged dialogue showed a more insightful purposeful side of him that was quite unexpected. Gears of War’s Cole, though fueled by the jockish life-of-the-party energy, featured a similar level of depth.

The signs of growth have shown in Crysis’s Prophet and Starhawk’s Emmet Graves where the lead just happens to be Black. Everywhere from Mass Effect’s Jacob Taylor and David Anderson, to Left 4 Dead 2’s Coach and Rochelle, to Half-Life 2’s Alyx and Eli Vance, each character was fleshed out as a person without paying too much attention to their skin color.

No comments

Post a Comment